THIS ARTICLE CONTAINS SPOILERS

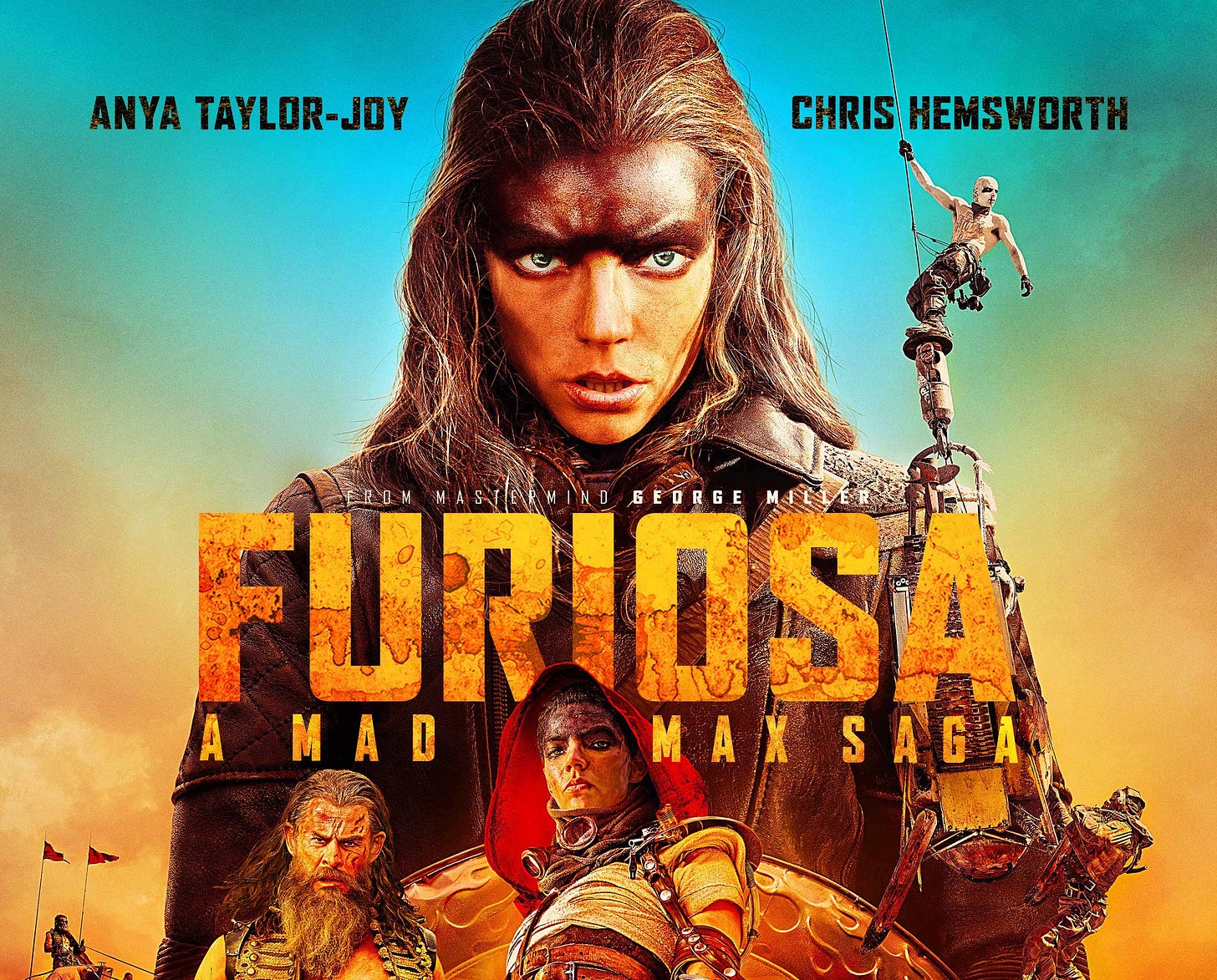

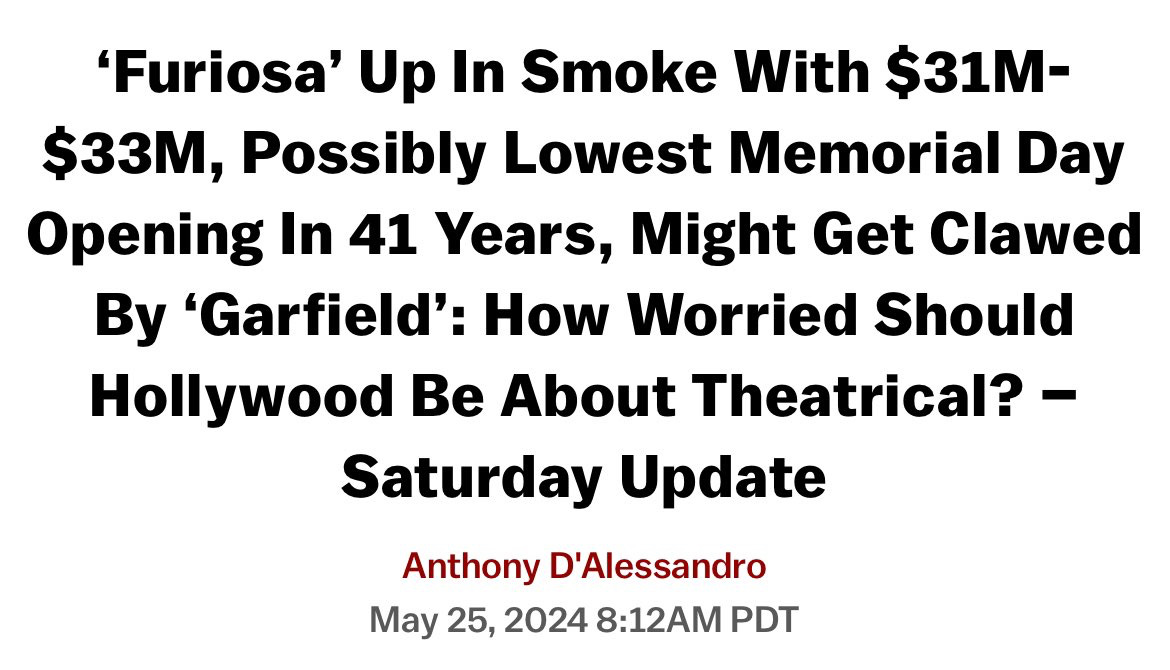

“Furiosa”, the sequel to the popular 2015 action film “Max Max: Fury Road”, bombed this weekend at the box office.

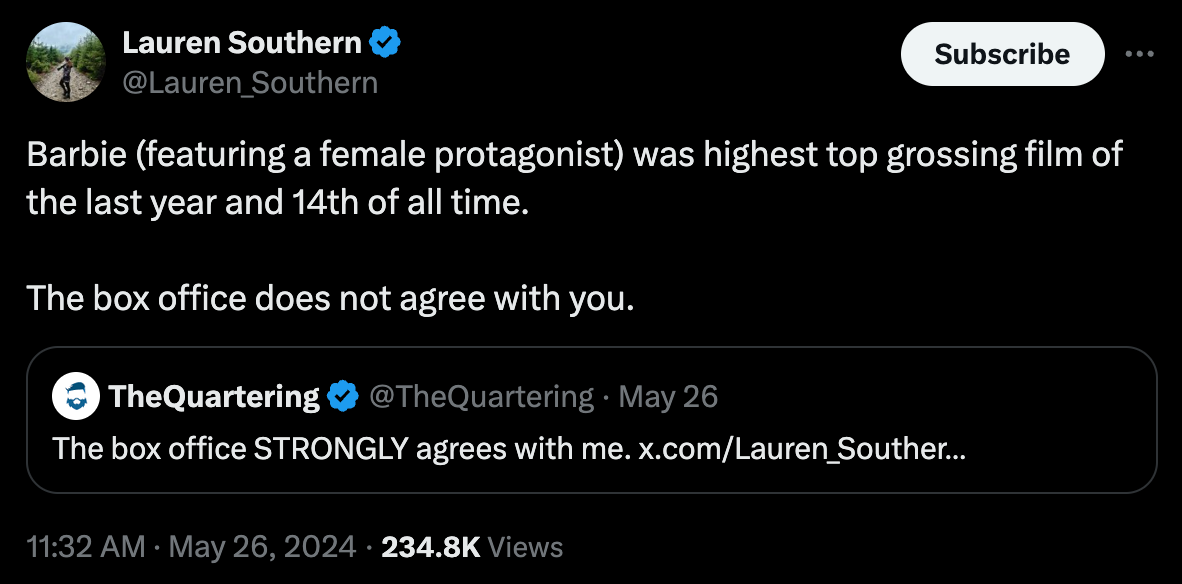

Many on Twitter/X attribute this to audience fatigue with female protagonists, as “Furiosa” stars Anna Taylor-Joy in the title role.

Filmmaker Lauren Southern instead claimed that audiences are craving films with better writing, regardless of the sex of the protagonist.

But I believe there are two key reasons why action films with female protagonists fail, and they absolutely should fail.

Furthermore, we shouldn’t be the least bit troubled by it.

The reasons are interrelated, and together they explain why we should celebrate these films’ failure as conclusive proof that no matter how the woke try to convince us otherwise…

Men and women are different.

Men and women have always been different.

Men and women will always be different.

The deep-seated human passion for story proves it.

Reason 1: We Rightly Abhor Violence Against Women

In any good comic book or action / adventure film, the threat of physical violence against the male hero’s body comprises one of the key points of tension in the plot.

“If the hero makes it out alive, and wins the day, will he still have the ability to function?” is the question the audience is unconsciously asking. Because if the hero lives but ends up disfigured or disabled, we don’t count that as “victory.” The conclusion has an ambiguous quality instead.

Yes, the hero won but at the cost of his ability to be a hero. So we’re left asking, “Was it all worth it?”

The final scene of Season 1 of HBO’s classic series “True Detective” illustrates this tension. In not so many words, Rustin Cohle (Matthew McConaghuey) is reflecting with his partner Martin Hart (Woody Harrelson) about the answer to a single question:

Was all the suffering they went through individually and together—including Cohle’s near death—worth it?

This works as a creative choice. But complicated emotions like this are not what mainstream audiences seek out summer action films for.

A less complicated example of the bodily threat faced by male heroes is found in the “Rocky” series, where Sylvester Stallone as Rocky basically spends six straight movies blocking punches with his face.

In “Rocky IV” (1985), he faces the Russian boxer Ivan Drago, played by Dolph Lundgren, who famously says: “I must break you.”

The threat is not just that Rocky will die during the encounter. Rather, that he’ll face total incapacitation.

In other words, a living death.

We see a similar threat from a villain in the 2012 Christopher Nolan film “The Dark Knight Rises”.

Batman (Christian Bale) faces Bane (Tom Hardy), during a battle midway through the film, which sets up Bruce Wayne aka Batman’s arc of redemption through the remainder of the story.

In defeating Batman, Bane lifts the comic book hero in the air. Then smashing Batman’s spine down on his knee, Bane utters the chilling line:

“Ah yes, I was wondering what would break first: your spirit or your body.”

These grave threats to the male hero’s body create tension and stakes for the action.

The hero’s task is not just to save the world and make it out alive. He must make it out intact, as well.

Compare this to female action stars.

If you watch closely, you will never see a female action hero take a squared-up punch from a male villain.

Female protagonists are invariably portrayed as faster, more agile, and more clever than their male counterparts. Using gravity-defying choreography and quick cuts, the heroines spin, dance, juke, jump, and twirl around their hapless male foes.

Meanwhile, you will never once see a female action protagonist take a closed-fist shot, like a man would.

Never.

The reasons should be obvious.

First, Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson) getting punched by Thanos would kill her. Even in a comic book universe with talking trees and robot raccoons, we can only suspend our disbelief so far.

Second, we know intuitively that male heroes are expendable. Of course we don’t want our male hero to die, but we also know that it’s his role to give his life if he’s called to.

We accept this as Captain America’s role to take on what humanity won’t, to accomplish what humanity can’t. (More on that later.)

But both these reasons pale in comparison to the most important one:

Seeing a female hero take a closed-fist punch to the face from a male villain would make us all sick.

No healthy human being wants to see a female action protagonist take a beating from Thanos like Captain America did above.

Hollywood may be full of ideologues, but they’re not stupid.

Our culture rightfully abhors physical violence against women. One week can’t pass without feminists decrying the threat of domestic violence that wives face from their husbands. More than two generations of public policy about marriage and the family has been shaped by that fear. Research the Duluth Model for more.

It would be hypocrisy beyond the worst fever dream of the most hardened blue-haired feminist to decry male-on-female violence at home, then celebrate it in action films as a step forward for “equality.”

Thus, it stands to reason that if women deserve protection from male violence in the household, they also deserve protection from male violence on the silver screen.

For the record, I agree wholeheartedly with both.

But for filmmakers wanting to promote female action protagonists, that poses a bit of a problem. If grave injury to a woman’s body can’t be on the table for the narrative—and shouldn’t be—that removes a meaningful part of the story’s stakes.

Audiences will know that the female protagonist is never in any real danger. So why get invested in the story? We know intuitively that the heroine will cakewalk through her toughest fights, which drains the dramatic tension.

Sure, the filmmakers can pump up the spectacle, or have the protagonist face environmental or CGI threats, like in the “Tomb Raider” game and series of films:

But without person-to-person stakes from a human antagonist more physically powerful than her… who cares?

Audiences clearly don’t.

“But Will,” you might ask, “What about the films that Lauren Southern mentioned, ‘Kill Bill’ and ‘Aliens’? They also have female action protagonists!”

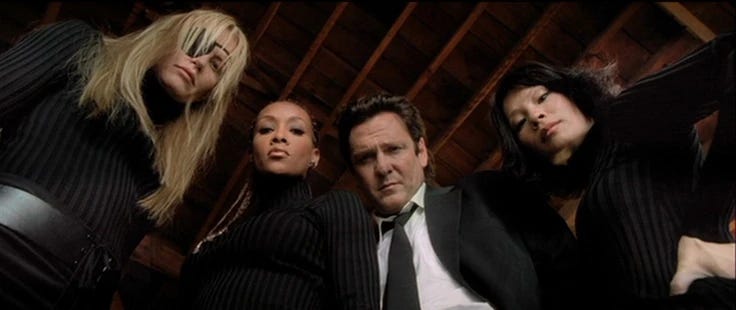

Careful eyes will note that the “Kill Bill” films star the character known as The Bride aka Beatrix Kiddo (Uma Thurman) taking out a team of mostly female assassins, the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad.

The primary action of the film takes place in female-on-female battles, with swordplay rather than fists. Because no one wants to see beautiful women punching each other.

And no one would believe it, either.

This female-on-female fighting even includes an intermezzo battle with the psychotic supporting character, the schoolgirl “Gogo Yubari” played by Chiaki Kuriyama.

The Bride faces down just two genuine male antagonists in the films. The first of those two battles ends before it even begins, with the Bride being shot in the chest with a shotgun blast of rock salt by Budd:

Why didn’t Budd use actual shotgun shells? Because (a) the rest of the story needed to happen, and (b) no one wants to see violence done to women.

The Bride’s second battle with a man is her climactic encounter with the titular “Bill” (David Carradine). The fight happens with them both seated at a table. After brief swordplay, the Bride vanquishes Bill with the mystical “Five Point Palm Exploding Heart Technique.”

Though Bill is a much older man than The Bride—far weaker than a supervillain like Thanos—the duo never get out of their chairs. Bill physically cannot throw a punch.

Tarantino is a clever filmmaker, but again he’s not dumb.

I’d also like to point out that the scene in “Kill Bill Vol. 1” that portrays the brutal attempted murder of The Bride is a sickening piece of cinema. In it, we see the depths of depravity that Hollywood has sunk to.

It passes solely because the violence happens in flashback. We know going into the scene that The Bride will miraculously survive and recover to begin her quest for revenge. The narrative stakes are already zero.

Regarding the film “Aliens” (1986), the film’s climactic battle happens between the mechanically-assisted Lt. Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and… wait for it… the Alien Queen.

Even in 1986, top-tier filmmakers knew that a female action hero couldn’t face down a male, even if that male were an alien. Only female-on-female violence could be considered acceptable.

Because let’s face it, no one in their right mind would sit through a film where a female action protagonist took a vicious beating on behalf of the human race.

Don’t believe me? Watch the first sixty seconds of this final showdown between Neo (Keanu Reeves) and Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving) from “Matrix: Revolutions” (2003).

Try to imagine a woman in Neo’s place.

I’m sorry, I can’t.

I won’t.

If you can’t either, congratulations. You’re a healthy man or woman.

Hollywood knows it, too. Because deep down we know that men and women are different.

Therefore, it’s not so straightforward to swap out a male hero for a female and have everything remain the same. Our natures as men and women rebel against it.

I hope they continue to. It will not be a hopeful sign if they don’t.

But there’s an even more vital reason why it’s not so simple to swap a female hero into action films.

Reason 2: Women Don’t Give Their Lives for Men

If you ask men about their favorite action-adventure films, you’ll discover that two films appear on almost every man’s list:

“Gladiator” (2000)

and “Braveheart” (1995).

Despite being set in two different eras, the stories have one key aspect in common: in each film, the hero gives his life in victory.

Those scenes are so powerful for men, I don’t even have to post the full video clips. Still frames will suffice to have an impact:

Every man knows these scenes.

They speak to something primordial within men, something woven into the fabric of our very being.

And these aren’t the only ones. Here are more. I won’t name what the films are. You already know them.

What do these scenes have in common?

They’re all men.

I can name countless other films with heroic sacrifices, like:

The Iron Giant (1999)

Sunshine (2007)

Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

Independence Day (1996)

The Last Samurai (2003)

V for Vendetta (2005)

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

Armageddon (1998)

Gravity (2013)

What’s going on here?

The answer is simple: they’re recapitulations of the Greatest Story Ever Told. That story is woven into the fabric of reality just like self-sacrifice is woven into the fabric of men. And they’re woven for the same reason, by the same Hand:

“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

~ John 15:13 ~

The line is spoken by Jesus Christ in the upper room to his disciples, on the evening before his death. He’s talking about himself as the man about to lay down his life for his friends, who are with him in that moment.

This heroic sacrifice is the model for all men. It’s the singular example that all the male heroes of page, stage, and screen emulate.

And here’s the key: there is no similar sacrifice for women.

The notion of a woman heroically laying down her life for civilization is silly on its face, for a couple superficial reasons.

First, women are givers of life. A civilization that celebrates the heroic sacrifice of women is a civilization that won’t be around for long.

Because a handful of men with dozens of women can repopulate a tribe with some effort on the men’s part. (They’ll live.) But a handful of women with dozens of men will still only be able to bear a limited number of children, leading to population collapse.

Thus, a woman ready to die in battle will harm her tribe more than she helps it.

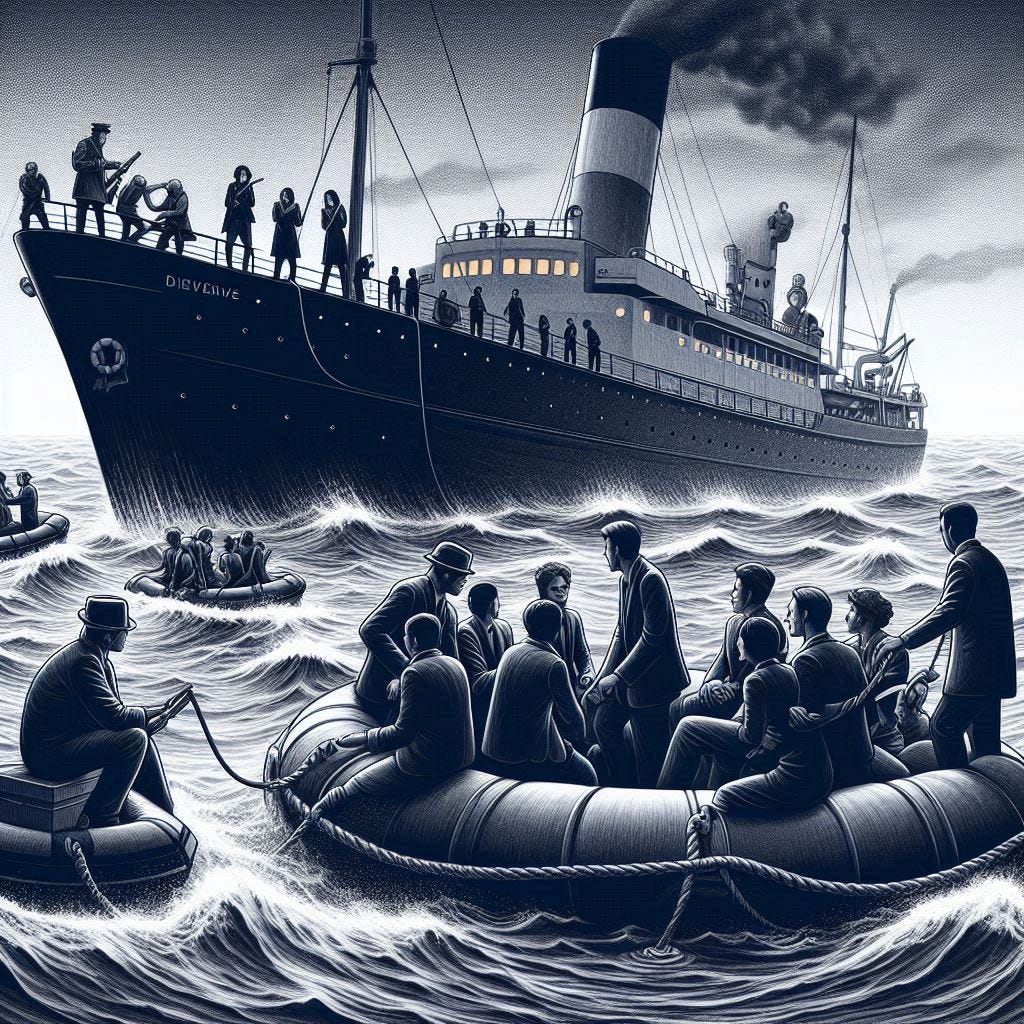

Second, the idea of “women and children first” is part of us as humans. If you don’t believe me, try this thought experiment:

To imagine a society in which it’s OK for men to fight against women and children for a seat aboard a life raft on a sinking ship.

I can’t. It’s ridiculous. I laugh when I think about it, and I can’t even articulate why!

In the same way, if a woman rushed off to give her life in battle, it would be silly for men around her to simply let her go. If we saw a scene like that on screen, we’d laugh. It would literally never happen.

Because just like a woman surviving a closed-fist punch to the jaw from a supervillain, there’s only so much disbelief we can suspend.

These two superficial reasons point to a greater truth that we all know, but that no one can articulate or that everyone fears to say:

A man sacrificing his life for society is not the same as a woman sacrificing her life. Because men and women are different.

So when Hollywood filmmakers try to insert a female protagonist into an action film, audiences can automatically assume two things:

She will not face the threat of near-lethal violence done to her body by an antagonist, especially not a male antagonist.

She will not give her life.

So… where are the stakes?

A female hero can’t get beaten within an inch of her life (thank God!), and cannot ultimately give her life at all.

If she can’t lose, the movie has ended before it’s begun.

And if a female protagonist gets in trouble, who would rescue her? A man? That would undercut the feminist message. A strong independent woman don’t need no man!

For all these reasons and more, audiences have every right to be bored of action films with female protagonists.

Because we already know the plot:

Plucky female hero is better than the boys, dating back to childhood.

She rises to a position of authority through wit and unusual skill.

She faces a threat from a powerful male villain who looks down on her for being female.

She cakewalks through her battles with him, even though he’s massively stronger than her.

Through a bit of luck and quick-thinking on her part—plus the villain’s arrogance—he is defeated.

If you ask me, this narrative can only be dressed up with so much spectacle before audience’s eyes get bored.

Even the explosions-in-the-desert franchise known as the “Max Mad” films couldn’t save this dying narrative style.

And I’m guessing that’s what the pitch for the film was. More of this:

… except with a female hero. Who’s also bulletproof.

Because no one wants to see a woman in a mask like this, strapped to the hood of a car, exposed to the elements, being harvested for her blood.

Because that would be demeaning.

For a final bit of evidence, I submit to you this year’s blockbuster film, “Dune 2” directed by Denis Villeneuve and starring Timothy Chalamet as Paul Atreides. According to industry sources, the film has grossed over $700 million dollars worldwide, so far.

If you haven’t seen it, I won’t spoil the ending. But suffice it to say, the climax of the film features a graphic knife fight between Paul and the psychotic villain Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen (Austin Butler.)

If you knew who was going to win this fight—or at least, if you knew who wouldn’t lose—would you care?

Then don’t be surprised if audiences don’t care either.

Instead, simply accept God’s glorious truth: Men and women are different. We have different roles and different responsibilities.

We’re each called to give our lives in different ways, for different things, and for different reasons.

So let’s not pretend that it’s so easy to swap out one sex for the other.

If you ask me, Hollywood’s attempt to do that is what’s really demeaning. Not just to men and women on screen, but to audiences, as well.

Maybe they’re finally admitting it.

Will Spencer is the Host of the Renaissance of Men Podcast (soon to be the Will Spencer Podcast), and is active causing trouble on Twitter and Instagram. Become a paid subscriber to this Substack for exclusive interviews and more.

Great insight here Will.

The principles here can be extrapolated into a number of different areas of life--pastors, entrepreneurs, and more. These kinds of men put themselves in the middle of a target, and unlike Hollywood, there is no director to stay Thanos' hand.

These kinds of men, especially pastors, get hit. They get attacked. They say things that are offensive to worldly sensibilities and become as Paul was: "To the present hour we hunger and thirst, we are poorly dressed and buffeted and homeless, 12 and we labor, working with our own hands. When reviled, we bless; when persecuted, we endure; 13 when slandered, we entreat. We have become, and are still, like the scum of the world, the refuse of all things."

This state and this domain is, frankly, unbecoming of a woman. It is not within the nature of a woman to get hit and endure the constant low-grade pain of an earth that resents our toil. Her pain is acute, intense, and over quickly; and it produces life.

Weak men give up and let women become the protagonist. Good men endure. Great men conquer.